He traces her shadow with his shoe… the swim instructor can’t quite pronounce his name so instead calls him “Subaru”… when he was three or four she left them behind at a video store: There is no lack of faithfully recalled memories on Sufjan Stevens’ seventh full-length Carrie & Lowell, but they can’t bring back the past. If time heals all, then what explains the pains of looking back? After the death of his mother in December 2012, Stevens was confronted with the reality of her loss for a second time, having been abandoned by her at a young age due to her mental illness and drug abuse. “Now I want to be near you,” he sings on “Eugene.” “Now I’m drunk and afraid/ Wishing the world would go away.”

Carrie & Lowell has been billed as a return to Stevens’ “folk roots” after a series of projects based more on experimentation than experience. The sound has elements of Seven Swans, his bare-bones 2004 album of spare, serene psalms – but rather than feel lifted by Stevens’ verses, we’re brought down to human scale, where doubt gathers in the corners of grieving, believing minds. His lyrics are as heavy as a corpse, the music as weightless as a spirit. He’s singing to be sure, but these aren’t songs; instead, they’re midlife symphonies to a God who may not hear his prayers.

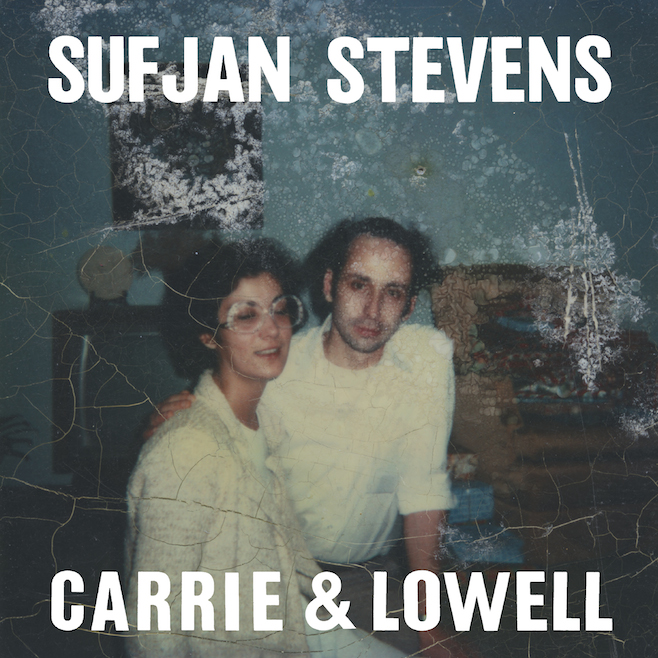

The title characters construct the album’s narrative as much as the record’s narrator. Carrie, Stevens’ mother, haunts each track like a ghost; Lowell Brams, Stevens’ stepfather, plays an important role both on tape and in the artist’s real life, as he currently runs Asthmatic Kitty, Sufjan Stevens’ record label, in addition to taking care of the young Stevens and his brother growing up. That history and honesty inform the album: When Stevens nails specific details, his tracks rise above the level of simple observation into allegory, as errant minutiae or little souvenirs turn into something more than what they appear at face value, with Stevens’ pain pushing Carrie & Lowell into territory refreshingly free of artifice after pouring his soul into falsified containers. “With this record, I needed to extract myself out of this environment of make-believe,” he told Pitchfork in an interview. “This is not my art project; this is my life.” By relinquishing control over his ambitions, Sufjan Stevens has inadvertently made the best album of his career.

Yearning for intimacy with Carrie & Lowell’s missing figure is what underlines Stevens’ pain most: Death has foreclosed the possibility, however, rendering Stevens hopeless. On his LP’s bleakest vignettes Stevens doesn’t flinch when describing his self-destructive behavior, as on “The Only Thing,” where “signs and wonders” are all that keep him from an early grave, be it through car wreck or razor blade. Suicidal thoughts may be held at bay, but depression rears its head in other ways. Stevens “copes” unsuccessfully through addiction, masturbation, and contrition, but ends up feeling empty.

Though this material could easily descend into the maudlin, Stevens and his collaborators – Thomas Bartlett, Sean Carey, Laura Veirs, and others – aim for something more complex in their meticulously layered but delicate arrangements. Without having to formally announce it as an addition to Stevens’ now aborted “Fifty States Project,” Carrie & Lowell also tells the story of Oregon: a place where the songwriter and his family made childhood summer trips, and one that pops up in references to the Lost Blue Bucket Mine, Spencer Butte, or the Tillamook Burn.

Carrie & Lowell’s biggest question is about music-making itself. It arrives on “Eugene,” – an uptempo number that masks the need for connection behind cheerfulness. Stevens is unable to hide his true feelings in his lyrics, however, which alternate between wistful reminiscence and lubricated, lugubrious soul-seeking: “What’s the point of singing songs/ If they’ll never even hear you?” He ends the song abruptly after these lines not because he’s scared of what the answer might be, but because he wants a response he’ll never get. Stevens knows there’s a point, and he replies to his own question at the end of the next song when he sings, “We’re all gonna die,” repeatedly. You can’t bring back the past, but Carrie & Lowell comes close to recreating it.

Sufjan Stevens returns to Detroit for a hometown performance at the Masonic Temple on April 27. Purchase tickets here. Listen to Carrie & Lowell below: